ELEMENTARY

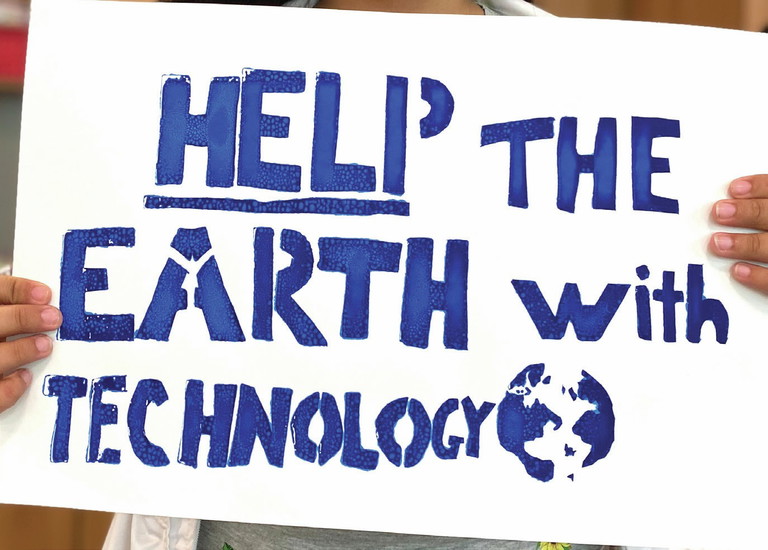

América S., Help the Earth with Technology, grade five.

Ariel Kay

Effective art education guides students to think critically about the world around them. Students learn to analyze, deconstruct, question, wonder, and imagine. When educators ask students what they desire to understand about the world and what they seek to change, we open up young minds to the possibility of positive social change.

Project Focus

Examine artwork and political posters from artists who advocate for a cause, such as activists Melanie Cervantes and Jesus Barraza of the graphic arts collaboration Dignidad Rebelde (see Resources). Discuss how these artworks were created with connections to communities and demands for justice.

Introduce terms such as community, advocate, culture, ethnicity, and identity, and discuss how these artists implement them in their work. I use the following definition for identity: who you are, how you view yourself, how the world views you, and who you hope to be.

When educators ask students what they desire to understand about the world and what they seek to change, we open up young minds to the possibility of positive social change.

Selecting a Community Issue

Students are asked to choose a topic that interests them based on their experiences in their communities (local or global). This topic becomes their community issue to address. Students can also choose something positive within their community in an effort to make this curriculum more asset-based.

Once students have chosen or created a community solution to their topic, they synthesize their ideas into a slogan through class discussions, peer collaboration, and teacher feedback. Some questions I use to inspire students include:

- Who is your community? What does your community need?

- What makes you sad or mad in the world? What brings you joy?

Stencil Compositions

After their slogans are formulated, students receive 12 x 18" (30.5 x 46 cm) mixed-media paper to create a giant stencil for silkscreen printing. Using rulers, students mark a border on all sides about 1" (2.5 cm) wide to avoid cutting too close to the edges. Students choose landscape or portrait orientation and brainstorm their composition, deciding whether to have their text above, below, or split around their images. We look back at the Dignidad Rebelde posters for examples and inspiration.

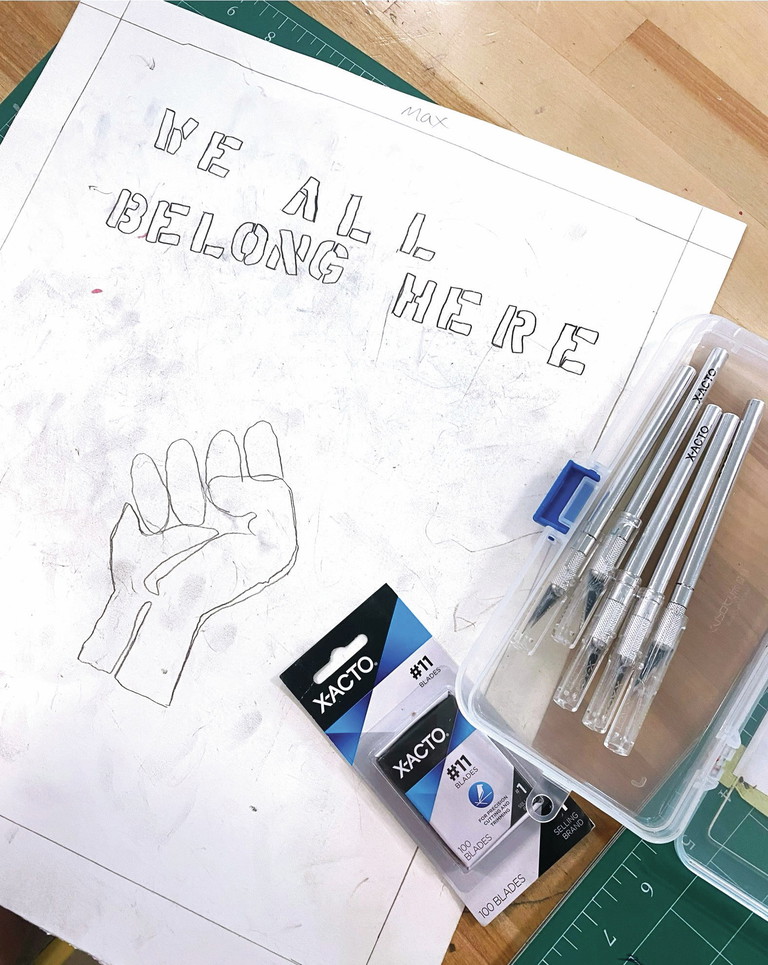

Max, We All Belong Here, work in progress.

Students are then provided a collection of alphabets in various fonts, as well as stencil images of hearts, globes, plants, animals, people, hands in various positions, brains, eyes, lightning bolts, shooting stars, food, and houses. Students can also request for images to be printed if they donʼt see their topic represented.

Students use carbon transfer paper to trace the letters and images to their papers. An accommodation that some students require is typing their slogan into a Word document in a stencil-friendly font and printing it so they can transfer the slogan to their paper without having to place letters individually.

Craft Knives and Safety

After transferring the images, we cut out each letter and shape. I provide students with safety parameters for using craft knives, such as capping the blade when not in use, paying attention to where their non-cutting hand is and cutting away from it. We use cutting mats to protect the tables and make cutting safer.

I explain that you need to press firmly through the paper and cut along your line. We discuss making “bridges” to keep the circles in certain letters from disappearing. For example, if you cut around an O, you may lose the center if you donʼt create a bridge to hold it in. Cutting these stencils can take time, especially if students are new to using craft knives.

Jocelyn S., grade five, screenprints with visiting artist Delilah Knuckley of Bibliographia, photo by Ariel Kay.

Silkscreen Printing

Visiting artists come to the art room to help out with the silk-screening process. We print studentsʼ stencil compositions onto poster paper—about 12 x 18" or slightly larger. We tape off the screen to cover any area larger than the posters being printed. Some years, we used just one color of ink; other years we used two colors to create a gradient. Students print their stencil twice, creating two posters. An adult assists each student in moving the wet stencil to a painting mat to the drying rack alongside the prints.

Project Culmination

We proudly display studentsʼ artwork at their fifth-grade graduation. In the past, this project was so well received, it was part of a public neighborhood art show.

Itʼs inspiring to watch studentsʼ families and the school community honor their messages. This past year, I announced to a cafeteria filled with proud family members, “We must listen to the youth. They know how to positively change the world. Debemos escuchar a la juventud. ¡Ellos saben cómo cambiar el mundo de manera positiva!” In honor of studentsʼ visions for a better future, I continue to present their artwork and spread their messages.

NATIONAL STANDARD

Connecting: Relating artistic ideas and work with personal meaning and external context.

Ariel Kay is an art teacher at Goralle Elementary School in Austin, Texas. arielkay@txstate.edu