MIDDLE SCHOOL

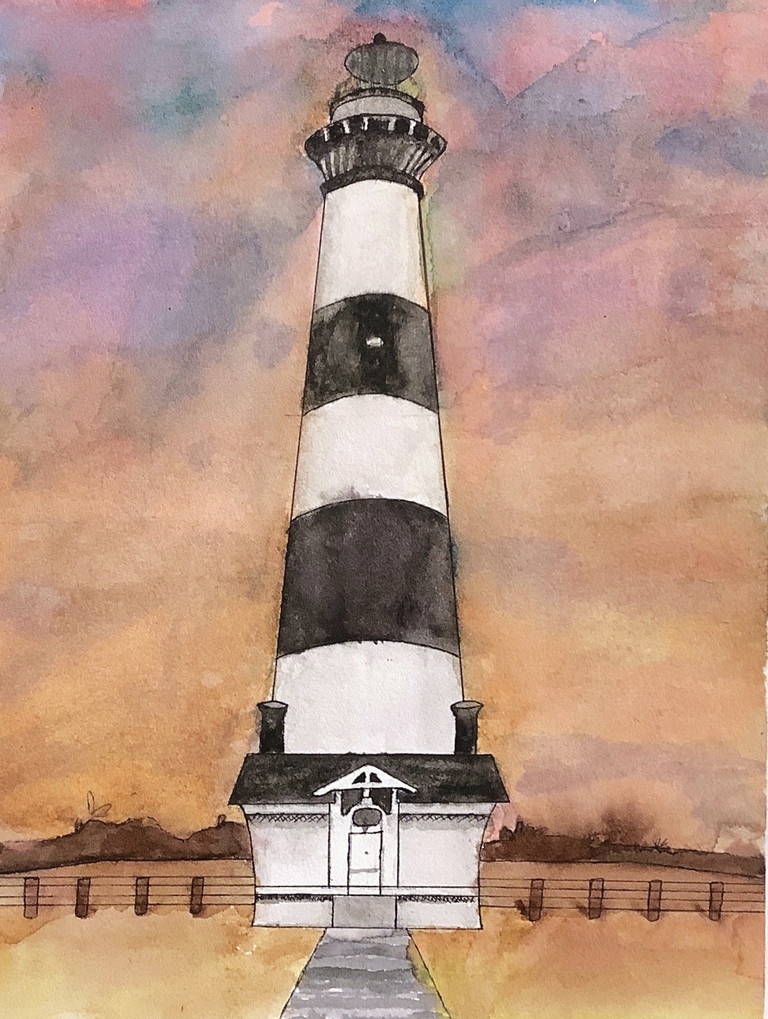

Sean J., lighthouse watercolor, grade eight.

David Anderson

The art room is a space that provides opportunities for students to build a unique set of skills while they convey their ideas and feelings through varied modes of expression. Because of this, art class can be a time when students have wonderful and awkward periods of selfdiscover y and where they can form healthy peer relationships.

A challenge that I’ve experienced over the years is balancing the need for skill development while providing that space for personal expression. When student work consistently looks the same, it can be difficult to justify implementing a project that doesn’t provide personal connectivity to the student.

I want students to relate to the subject matter they are rendering in their art. We know students are more likely to be enthusiastic about their work if the subject matter is relatable. I often wonder if a collective observational exercise can provide an opportunity for students to express themselves as individuals.

Lighthouses as Subject Matter

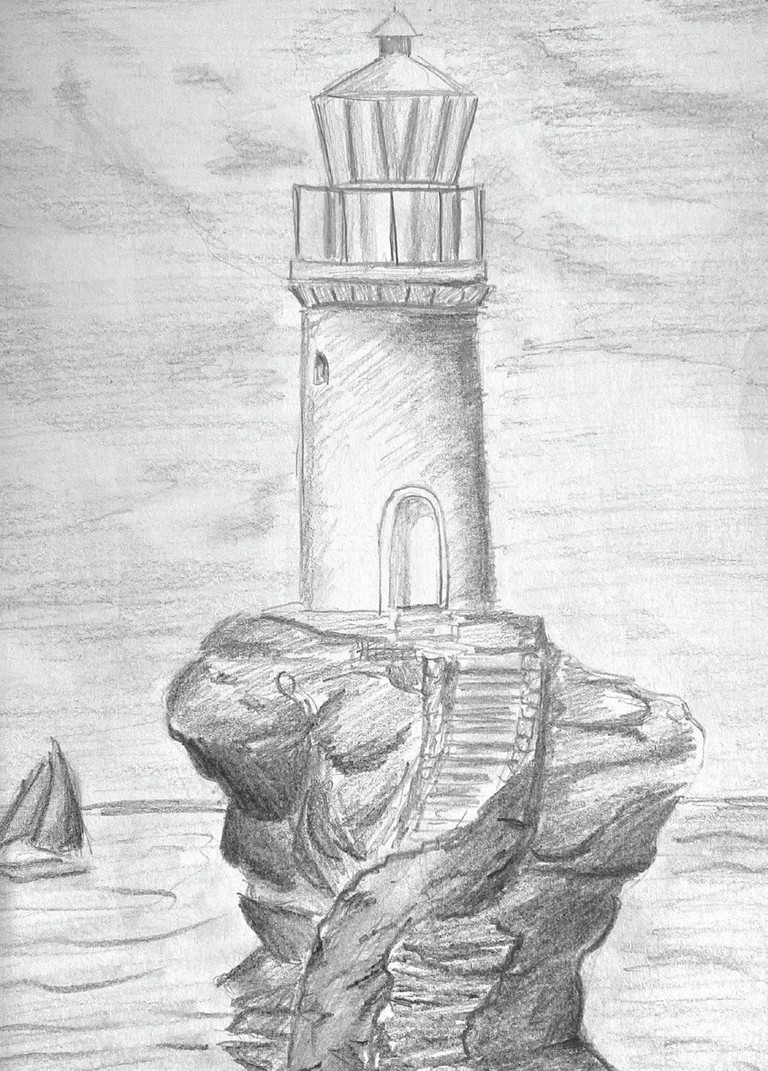

Over the years, I have incorporated lighthouses as a subject at all three grade levels: sixth grade (clay), seventh grade (drawing), and eighth grade (watercolor illustrations or pastels). The lighthouse is a great example for showing students how simple shapes—a cylinder in this case—can be found in their everyday lives. Furthermore, middle school is a great time in skill development to tackle the complexities of form through drawings and paintings.

Students are prompted to reflect on who or what serves as the “lighthouse” in their life and how this person or thing protects or guides them.

When viewed collectively, the final products for each of these units might suggest there is room for students to be more creative with the materials. These lessons are grounded in skill development, but they are also opportunities for students to connect to the subject matter in meaningful ways.

Symbolism in Hopper’s Paintings

Edward Hopper’s lighthouse paintings are great examples for this lesson, and they also provide a springboard for discussing the purpose of a lighthouse. Students discuss how lighthouses were designed to guide ships through rough waters and challenging weather conditions, providing hope for those in distress.

Timmy E., pencil drawing, grade seven.

Jack H., clay lighthouse, grade six.

Joshua K. and Desmond M., grade eight, work on their watercolor compositions.

Beyond his lighthouse images, Hopper’s collective work is also worthy of inquiry. His paintings consistently evoke themes of isolation and hope, providing an excellent catalyst for student-led discussions. These themes, perhaps more than ever, are at the forefront of student life.

After viewing several images, students begin to see a common thread, specifically with paintings that include the human figure. They observe Hopper’s consistent minimal use of objects and figures illuminated by a distinct light source.

Students comment that the figures in Hopperʼs paintings appear to be disconnected from one another, a theme that is relevant to middle school students in this post-COVID era. While Hopperʼs work is sometimes interpreted as sad or depressing, it is not without feelings of hope. Hopper’s depiction of light helps to move the class discussions in this direction.

Ben B., oil pastel drawing, grade eight.

The Light in Your Life

At the conclusion of these discussions, students develop an eight-sentence artist statement to accompany their final work. They are prompted to reflect on who or what serves as the “lighthouse” in their life and how this person or thing protects or guides them.

Many students choose traditional guidance figures such as family members, and I am always impressed by their passionate declarations:

“If I lost my mom, I would have lost one of my favorite people in the world. She is so loving and caring and a pleasure to hang out with. I can always count on my mom to love and guide me.” “My grandma is the lighthouse in my life because she always opens new paths for me. She guides me through things I don’t know yet. When studying African American history, she gave me good resources for stories about black cowboys.”

Students also choose activities they are involved with outside of school:

“A lighthouse in my life is swimming. It allows me to clear my mind from any worries I may have. It helps direct my mind to be happier, more focused, and productive.”

Some reflect on personal spaces: “A bed may not seem like much, but it guides me through all my troubles and allows me to enter meditation, where I can forget about the day and relax.” Others can be a bit more abstract: “The lighthouse in my life is the dream of what I want to become. Without a dream, one wanders directionless, lost in the darkness.”

Students can choose any media they would like to express their ideas. The finished works are displayed in the halls, along with students’ artist statements. On a few occasions, students have revealed components of their life that they did not want to share publicly. In these instances, I honor their request.

Reflections

These submissions offer a unique insight into the student that helps build connections to their world outside the classroom. One of the most significant rewards as a teacher is watching students, teachers, and parents take the time to read the write-ups and, in doing so, discover something endearing about the artist behind the work.

NATIONAL STANDARD

Connecting: Relating artistic ideas and work with personal meaning and external context.

David Anderson is a middle-school art instructor at the Gilman School in Baltimore, Maryland. danderson@gilman.edu; unfinishededucation.com

The Lighthouse as a Symbol