HIGH SCHOOL

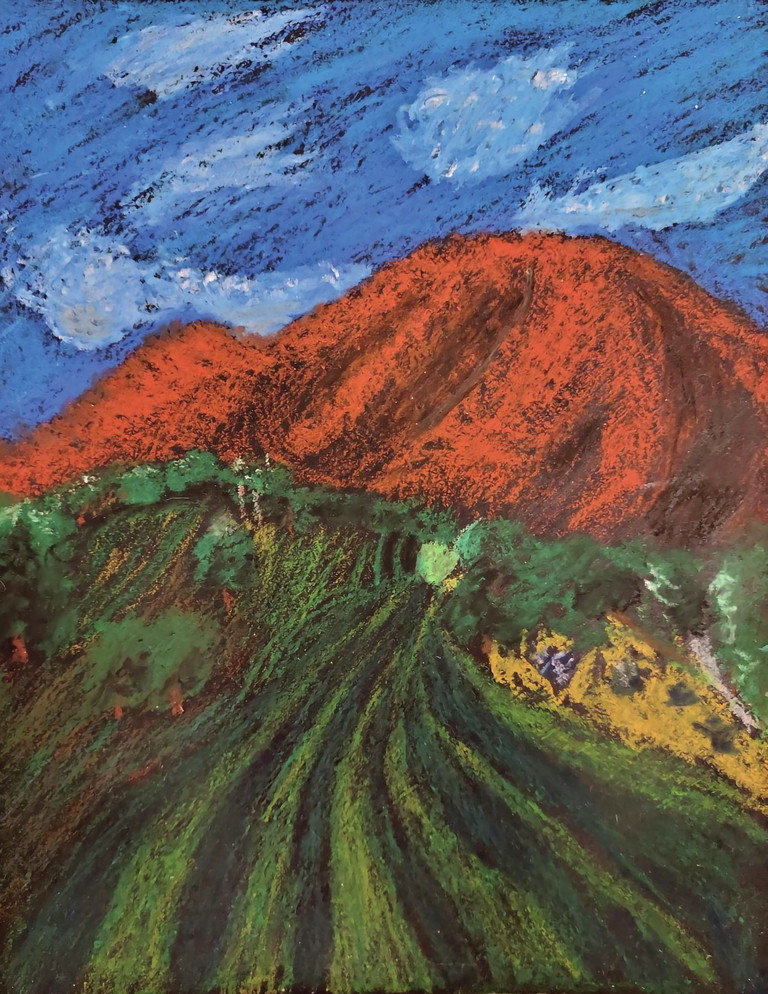

Davis O., landscape.

Davis O., nonobjective companion piece.

Betsy DiJulio

As my Art 1 students were finishing their large and technical acrylic paintings, I was casting about for the next challenge. Since they were enjoying working with color but needed a break from paint mixing, oil pastel seemed like an ideal medium. It’s rich, creamy, and painterly, yet it relies largely on drawing skills like direct mark-making and layering of color. We had been working with a high degree of realism all year, so I thought a more expressive and intentionally abstract approach would be a nice change.

Since students had been working on portraits and still lifes all semester, I thought landscape would be a good subject to tackle, provided we could find enough copyright-free images to work with. I need not have worried because there are more copyright-free images online than ever before. Plus, these particular students had traveled extensively and had lots of landscape photos on their camera rolls.

Handscapes

I had learned about handscapes (landscapes the size of one’s hand) from a visiting artist, and I thought pieces this size would be a nice contrast to the large paintings students had recently finished. I decided that postcard-like pieces about places we all long to visit or revisit after the pandemic would be relevant. And that’s how the project Anywhere but Here got its name.

After they get grounded in some basics, I let students experiment and make those exciting discoveries that enrich both the artistic journey and the destination.

The slideshow also included minilessons in oil pastel blending, layering oil pastels over each other and over acrylic underpainting, and sgraffito with colored pencils on top of both.

Students chose copyright-free photos or images from their camera rolls, analyzed the basic shapes, and created 4 x 5" (10 x 12.5 cm) thumbnail sketches in graphite.

Next, students used acrylics to paint two 4 x 5" rectangles in their sketchbooks and created oil pastel and sgraffito thumbnails of each to determine which underpainting worked best. They could alter the colors, provided they did it with intention. Lastly, they transferred their thumbnails to the larger paper to create their finished pieces.

The Nonobjective Companion Pieces

For our nonobjective pieces, I introduced the work of Kay WalkingStick through a journal entry prompt that included a YouTube artist profile on her called “Hear My Voice.” WalkingStick views her diptychs not as opposites but as two different ways of representing the world that enrich each other. Sometimes she uses figures opposite her landscapes, sometimes patterns based on her Native American heritage, and still other times simple, universal shapes. It was the latter that we used as a springboard.

Julia W., landscape and nonobjective companion piece.

The slideshow also included minilessons in oil pastel blending, layering oil pastels over each other and over acrylic underpainting, and sgraffito with colored pencils on top of both.

Students chose copyright-free photos or images from their camera rolls, analyzed the basic shapes, and created 4 x 5" (10 x 12.5 cm) thumbnail sketches in graphite.

Next, students used acrylics to paint two 4 x 5" rectangles in their sketchbooks and created oil pastel and sgraffito thumbnails of each to determine which underpainting worked best. They could alter the colors, provided they did it with intention. Lastly, they transferred their thumbnails to the larger paper to create their finished pieces.

The Nonobjective Companion Pieces

For our nonobjective pieces, I introduced the work of Kay WalkingStick through a journal entry prompt that included a YouTube artist profile on her called “Hear My Voice.” WalkingStick views her diptychs not as opposites but as two different ways of representing the world that enrich each other. Sometimes she uses figures opposite her landscapes, sometimes patterns based on her Native American heritage, and still other times simple, universal shapes. It was the latter that we used as a springboard.

Connecting WalkingStick’s approach to anthropologist Angeles Arrien’s theory of the five universal shapes, I challenged students to create the second piece of their diptychs by featuring one or more of the shapes, chosen for their meanings, in a way that correlated visually with their landscapes—same underpainting, same color palette, same markings, etc.

Arrien’s research, which spanned thousands of years of art history around the world, revealed that artists return to the same basic shapes again and again: the circle, the square, the triangle, the equilateral cross, and the spiral. These shapes often have similar meanings, such as wholeness; stability and foundation; goals, dreams, and visions; relationship or intersection; and growth and change, respectively. So, the reasons students had for selecting their landscapes drove their selection of shapes. After they get grounded in some basics, I let students experiment and make those exciting discoveries that enrich both the artistic journey and the destination.

NATIONAL STANDARD

Creating: Conceiving and developing new artistic ideas and work.

RESOURCES

Betsy DiJulio is an art teacher at Norfolk Academy in Virginia Beach, Virginia. bdijulio@norfolkacademy.org

Anywhere but Here